Django-CMS, the best content management system (CMS)?

- Article en françaisAt Naeka, we hardly ever make simple websites; we focus much more on an application-based model, and each application brings with it its own special characteristics, complexity and surprises - giving rise to interesting and challenging projects that we enjoy working on. Generally, our needs are such that we tend to manage everything for ourselves, so that for many of our projects we only use Django for the backend, leaving the frontend to JavaScript frameworks such as Angular or Ember (which is our favorite). Nevertheless, certain clients' requirements include the ability to manage their own web app, allowing it to develop as their organization grows. This means not only modifying the content but also giving the client the ability to modify the structure and respond dynamically without having to restart the development process. We were familiar with the previous versions of Django-CMS, having had experience of working with them in the past. At the start of the year, we discovered, tested (and kept on testing), then learned to love the brand new major release of Django-CMS, which was in its "beta 3.0" version at the time. Since it came out, we have used it in the development of two web apps. In some ways, this article is an account of a fascinating journey of (re)discovery, in view of the fact that there are so many new features and improvements.

Django-CMS is open source, with a large number of people contributing to its development, many of them in response to Divio, a web development agency based in Zurich that has initiated many other Django projects. And what could be better for this agency than to base the program's developments on the express requirements of their significant customer base? Success and recognition come from the fact that, in addition to seven years of loyal service, the CMS has been widely adopted within the Django community.

What does the CMS allow you to create?

Django-CMS perfectly manages to provide all the usual functionality of a CMS, but it's worth knowing that:

- Hierarchical page structure

- A powerful yet simple content editor

- A media manager, drag and drop and one-click operations

- A publication workflow, moderation by super users and highly specific user permissions and roles

- Version control, supported by roll back tools

- Sandbox environment isolating the live and draft versions and content preview

- Multilingual page versions with automatic and configurable fall-back pages

- Search engine

It employs the same philosophy as Django, building on its functions; for instance, management of the “Sites Framework” that allows content originating from a single source to be incorporated into multiple sites. It also benefits from the Django administration tool, which allows a configuration interface to be generated automatically, meaning that extensions can be developed particularly quickly. It has its own multi-level cache (for pages, menus, etc.) which is based on Django and which significantly reduces server loads in instances where certain pages may generate a large number of database requests. Finally, Django-CMS avoids needlessly reinventing the wheel and has managed to incorporate some extremely good Django apps for its own purposes, such as hvad for multilingual content, haystack for simple yet effective searching, mptt for hierarchic site structures and django-polymorphic for certain more esoteric modules.

The benefits

In a word: customization.

Django-CMS was designed from the outset as a core product that needed extensions to fulfill its potential. As the interface is very basic, there can be a steep and slow learning curve, but the upshot is that you never find yourself in a situation where functionality is lacking.

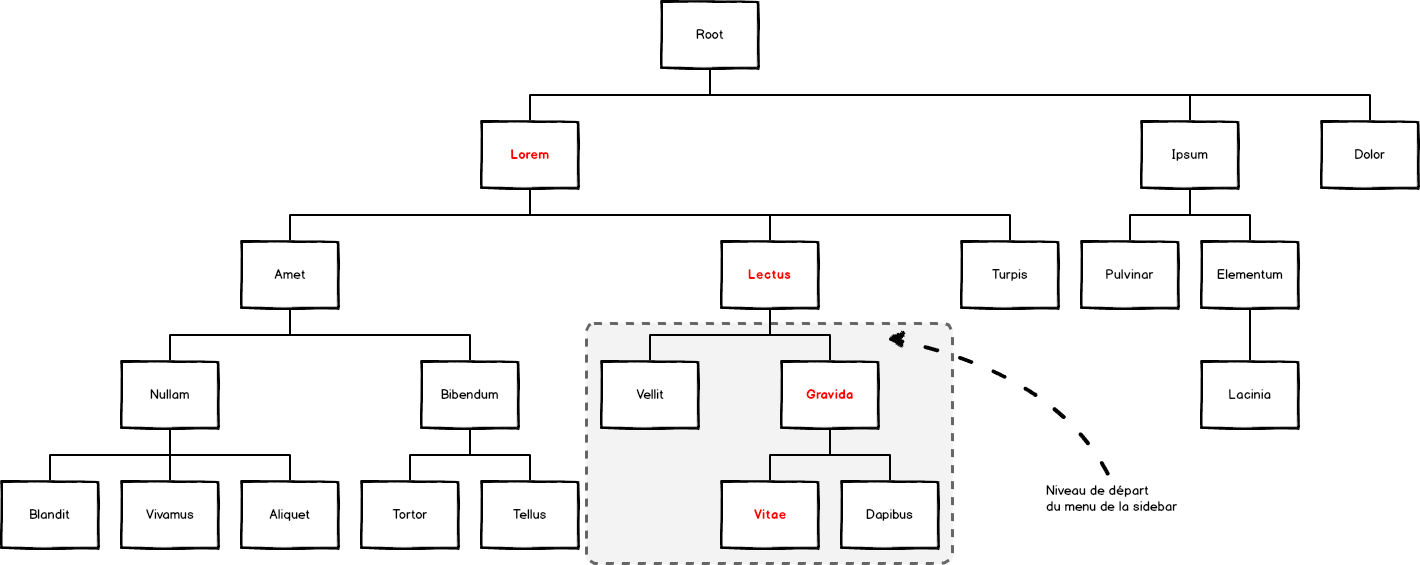

Their approach to menus is interesting: the menus contain the structure for the entire application. When a page is created, a menu entry is automatically allocated to it.

From that base, several options are provided to developers and integrators:

- A page may be included in the navigation hierarchy but need not be);

- Menus are generated automatically on several levels (making them easy to adapt for Bootstrap, for example);

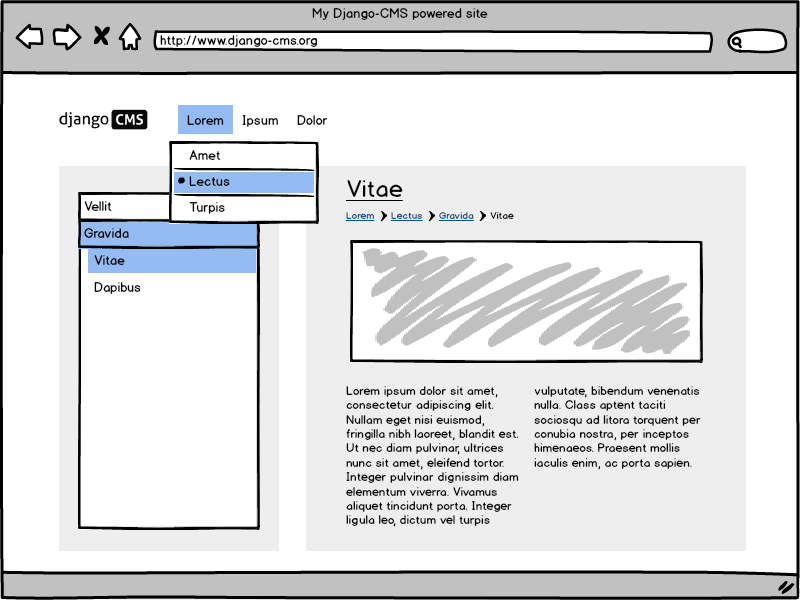

- The number of levels to be displayed can be customized, so it is perfectly possible to have multiple browsing zones;

- The main menu in a header can have one or two levels, giving fast and easy access to different categories;

- A secondary menu, in a sidebar for example, can have one or two levels based on the relevant context. As such, the menu on the second level of our site, will show the children of the current second level.

This gives a four-level navigation tree as shown:

can be simplified with the following approach:

The magical thing about it is that there is no coding required to get to his point, and many other usage cases can be achieved in the same way.

Menus use intelligently split templates, which allows the menu's default settings to be overridden, as a minimum to adapt the menu to suit the graphical toolkit that is deployed.

Finally, because some projects may require a different structure for a secondary menu (such as a sidebar) or for a dedicated menu for touch screens or small screen formats, it is possible to append a template argument to the show_menu tag (and all its derivatives).

In short, there really are no limits where integration is concerned and users are free to design a simple yet effective navigation tree that sits on top of a complex and highly nested structure. Nevertheless, it is important to bear in mind when developing with Python that the structure is based on MPTT and therefore it is important to ensure that this depth of hierarchy is not abused, which risks slowing the user experience as a result of excessively complex SQL queries.

Breadcrumbs are not used throughout but depending on the structure, they may prove to be a useful choice. Site management is simple and menu-driven and can easily be customized to meet any particular requirements.

Managing a site of static pages is utterly routine and fortunately, Django-CMS is not limited to that single task. In effect, it provides two methods to extend the CMS:

Plugins: which are basic, yet incredibly simple.

They may be placed at multiple locations throughout the site and may include a list of the last ten registered users, a PDF viewer or a Dailymotion reader, etc. Each plugin has its own template that is used to configure it via a popup that appears directly on the front end while running on top of the Django administrator: everything is generated automatically!) Each plugin also has its own view and template to display content and each can access the context of the page where it appears. As a matter of definitions, anything that appears in a place holder is a plugin, including text, links, images and columns. One of the most powerful and unique aspects of this version 3? Plugins can be nested, which creates a lot of opportunities such as sliders, etc!

"App-hooks": pulling out all the stops.

App hooks allow a Django app to be included as a descendant of a page in the hierarchy. Apps can be sourced from the developer's own project or from the thousands of existing Django apps that are available. The app's urlconf can be used directly to generate a navigation structure or can be recreated in a

cms_app.pyfile that contains all details of the app-hook's configuration.With app-hooks, the CMS is no longer bound by any limits and it becomes entirely possible to include highly specialized, custom-developed items in institutional sites.

There is so much that could be said about the numerous and varied possibilities, but even if we restrict ourselves to an abstract description, the prospect is quite daunting. That is why I invite you, if you would like to learn more about app-hooks, to regard this intense video presentation on app-hooks (56 min in length, by Martin Koistinen, a Django-CMS core developer).

After discussing customization above, it should be understood that absolutely everything can be modified: pages, menus (including at runtime, depending on the context), the admin interface and the "toolbar" which is useful for staff who administer the site.

One last benefit deserves to be highlighted: the API.

This is an internal API (don't think of it as equivalent to REST) which really makes it much easier to manage the CMS during automated processing operations. It's extremely simple but it contains the procedures that represent the right way to create a page, to publish (or withdraw) a page and to manage placeholders and plugins.

That has proved to be particularly useful on two occasions for two of our projects:

- When we were integrating a REST API (this time with Tastypie) we needed to publish or withdraw such and such page depending on whether or not certain objects were included.

- When we had to migrate content that had been created in Spip. Funky.

Django-CMS: avenues for improvement.

-

A generic system for a draft/live version that could be used for any app-hook with a

PlaceholderField. Currently, when a user edits the content of a placeholder, it is immediately reflected in the live environment. For the end user (who is not necessarily comfortable with technology), this behavior is not consistent with that of traditional pages or static placeholders, where users may edit their drafts at leisure, as many times as they wish before making a deliberate decision to publish by clicking on a button. Nevertheless this would be a fairly complex improvement to implement as it requires a different approach to be taken. Two placeholders would be needed (one draft and one public to adopt the terminology of Django-CMS, although it may be possible to use a mixin) but it is extremely important to revise the publication procedure, although I am afraid that may be far from a trivial task. -

Links to external content (created via app-hooks) from the text editor. In fact, it is impossible to create a link to the child object of an app-hook, even while attaching a menu to it. Admittedly this is for the simple and valid reason that the Link Plugin has a foreign key to a page. Nevertheless it is quite unsettling for users who may not make the distinction between a page within the CMS itself and a page that is managed by an app-hook. Other plugins such as “styledlink” aim to address this problem, but it is still regrettable that there is no solution right out of the box.

In conclusion:

Even though the Django-CMS interface won't revolutionize the world of content management systems, its comprehensive range of features and its extensive options for customization mean that it is a very good CMS that comes highly recommended. That is certainly why it is the most widely used CMS among the very good systems that run on Django (Mezzanine, FeinCMS or even the new, but highly promising Wagtail, to name but a few).

Moreover, its large user community, the support accessible via Google Groups and Stack Overflow and the comprehensive tutorials that are available mean that the system can be learned quickly and easily. The plugins are also simple to create and there is an existing range of reliable plugins that grows from day to day, serving as a source of inspiration when a level of complexity is reached that takes you beyond the level of the documentation or the tutorials.

Finally, we found that Django-CMS 2.x was quite difficult to access for certain users. Since the appearance of version 30, frontend editing and the CKEditor are clearer, simpler and more powerful.

To contact us directly you can simply send us an email at [email protected].